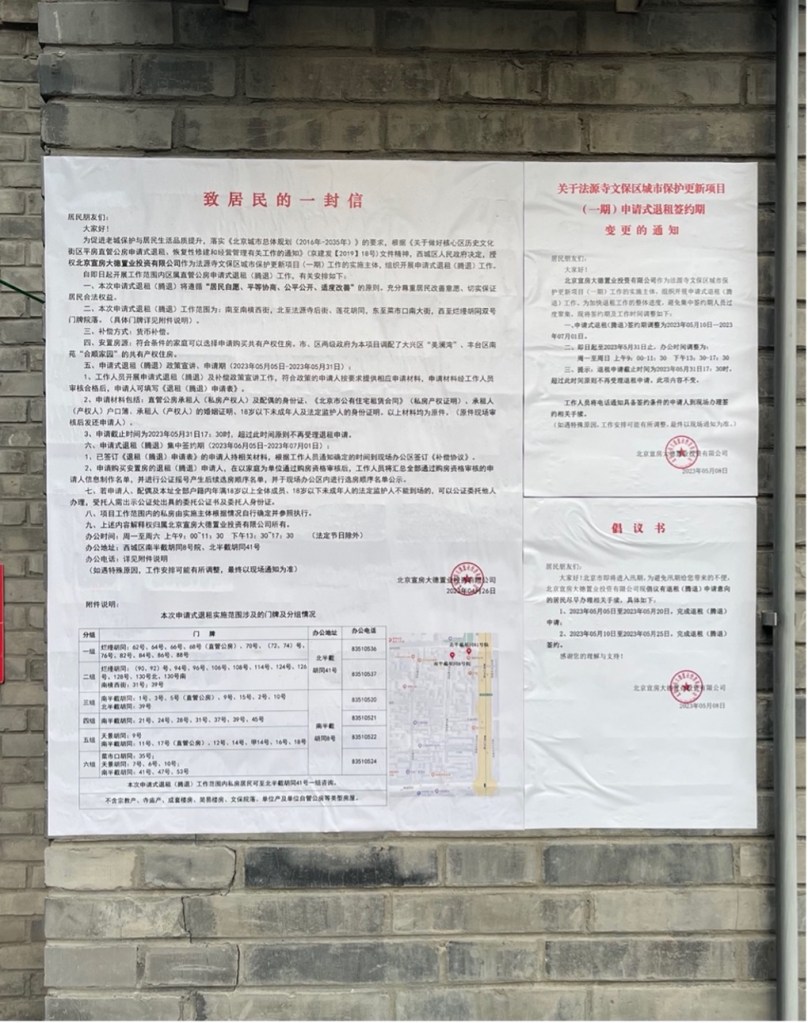

‘A letter to the residents’ – this is a notice, posted on 26th April 2023, on the walls of Fayuansi Heritage District (FHD). It serves to formally announce the commencement of the courtyard regeneration project within FHD and to deliver some essential rules of the process. According to the literal translation from Chinese, the notice stipulates that this project should be guided by the fundamental principles of “voluntary participation, consultation on the basis of equality, fairness and transparency, and moderate change to the neighbourhood”. Looking solely at this guideline, it seems that the early-stage radical demolition and reconstruction of the Beijing inner city has now ceased to exist. Instead, a new voluntary approach is being implemented, offering citizens a better position to exercise their right to participate in the regeneration process. However, there might be another version of the story beyond the official discourse.

(Photographed by the author in April 2023)

FHD is a hutong area in central Beijing, encompassing a total of about 16.16 hectares, and has many heritage protection units located within the district. On any given day at 4 pm in FHD, there are children joyfully playing with scooters, elderly sitting and chatting in front of courtyard entrances, and migrant construction workers riding in the hutongs to commute home. Indeed, the collective experiences and profound emotional connection to the place constitute the authenticity of FHD as a heritage (Madgin et al., 2018). Nevertheless, it needs to be careful not to excessively romanticize life in hutong, as this area is also a dilapidated part of Beijing, urging some form of redevelopment to improve residents’ living standards.

Behind those traditional double red entrance doors, the once tree-shaded courtyards are now filled with informal self-built additions due to the rising number of people sharing living spaces, leading to severe deterioration of the building condition. Moreover, although the municipal government has implemented infrastructure renovation in FHD in recent years, some households still lack private toilets and adequate kitchen spaces.

It is under this context that the new round of government-led regeneration projects is carried out. In urban China, most of the redevelopment is planned and implemented by the state, sometimes by the markets, whereas community-led projects are seldom observed and often fall short of achieving their intended results (Wu, 2016; see also Shin, 2014). Such narratives are quite prevalent in East Asia, where countries are often seen as ‘developmental states’ that rely on a state-led approach as the primary, and consistently successful, method to foster economic growth. However, as posited by many scholars, public participation plays a crucial role in solving complex and contentious problems, particularly when it comes to heritage conservation and regeneration (Innes and Booher, 2004; Atkinson, 2008). The previous infamous forced demolitions and reconstructions that occurred in the inner-city of Beijing serve as a highly representative counterexample (e.g. commercialisation of the Qianmen area and demolition of the Gulou neighbourhood)

Thus, the new participation approach becomes an interesting case for examining the government’s role as a developer or property holder and raises the question of whether or not residents have truly obtained their Right to the City. Some of the main modifications compared to the old approach include: (1) residents have the option to stay in the area; (2) Consultation with the community is required in the planning stage; (3) Homeowners should be able to select a real estate agency; (4) A clear regeneration and compensation plan must be made available to the public before implementation.

Yet the case of FHD shows that, except the last one, all of the other rules have been followed in a halfhearted manner. First of all, residents are granted the right to remain in the area, but this does not necessarily mean living in their current houses. Instead, households might be transited to other courtyards within FHD, allowing their current residences to be completely vacated for easier reuse by the authority. Putting aside the high probability that these houses will be reused by the elite groups, the alternative accommodations provided to current residents completely fail to reflect ‘community participation’ in the planning stage. “… Below is the toilet and kitchen, and above, there’s a loft for you to sleep. We, the elderly, already have illnesses, and it’s easy for us to fall down at night when we can’t see clearly,” a resident expressed in a street interview conducted in Chinese. For a community predominantly inhabited by the aged, it becomes evident that public consultation is lacking in such designs.

The flawed participation is also reflected in the choices available to households that decide to move elsewhere by purchasing government-assigned apartments with a financial subsidy. In the case of FHD, only two options for resettlement housing are provided. These are the Heshun Jiayuan and Meilan Bay apartment complexes, both located in the relatively periphery districts. When compared to FHD, which is in the heart of Beijing, the resettlement housing lags significantly in terms of both the quality and quantity of supporting facilities. Hospitals, in particular, are a primary concern for many of the elderly who face relocation choices, especially if taking into consideration the growing spatial inequality of access to medical services in Beijing (Zhao et al., 2020).

Property right is another major problem. Based on the relocation policy, all the government-assigned houses are co-owned by the residents and the government. Take the Heshun Jiayuan apartment complex as an example, which is one of the resettlement options for the FHD regeneration project; only 45% of the apartment’s ownership can be purchased and owned by residents. Consequently, these properties are not available for future private transactions. In other words, they can solely serve the purpose of residence with very limited potential for value appreciation. Whilst such a model aligns with the government’s principle that ‘houses are used to live in, not for speculation’, in reality, disputes concerning shared-ownership houses are commonly seen, particularly regarding issues like low housing quality, excessively high parking fees, and inadequate facilities.

It needs to be pointed out that these housing projects are predetermined by the authority, which means local citizens of the regeneration area are unaware of their choices until the notice mentioned at the beginning of this article is published to the public. This implies that although community participation has been constantly advertised by the local government, such participation can only be observed in the final implementation phase. Nitzky’s critique on this topic provides an interesting explanation. He argues that participation in China is 参加 canjia (to take part in), not 参与canyu (to engage in) (Nitzky, 2013). The distinction lies in that canjia refers to passive involvement or simply attendance, while canyu signifies active participation that generates contribution.

Moreover, the large number of migrant tenants residing in FHD faces an even complete exclusion from participation. Migrant workers who run tiny local businesses in central Beijing are never considered by the authority or the authorized implementation companies, as they are neither property owners nor seen as members of the community. This issue is connected to a deeply rooted social problem of China’s Hukou (household registration) system, thus adding another layer of complexity to heritage regeneration projects.

As mentioned above, indeed, the living standard in FHD, like many other dilapidated heritage areas in the inner city of Beijing, is urging for improvement. Yet for whom this improvement and redevelopment serve, and whether or not all residents are able to claim their ‘rights to the city’ – a notion proposed by Henri Lefebvre (1996) highlighting the role of urban inhabitants in shaping the city – throughout the regeneration process are perhaps the most important questions to be answered. Many local residents who have personally witnessed the history of Beijing’s inner-city redevelopment are well-acquainted with the evolution of urban redevelopment policies in the past decades. A currently prevailing sentiment among them is that the benefits provided by regeneration projects to common folks have gradually dwindled.

We can also understand the state’s hardship. But there are some problems that we truly cannot overcome … When I speak to the demolition company, [they tell us] ‘we are not here to solve your difficulties.’ (A random FHD resident participated in a street interview in May 2023)

Are the authorities vacating this place because they want to solve my difficulties or because they want to vacate it for their own use? Aren’t they doing this for the residents? … Then help me renovate the houses right where it is. (A resident of Xicheng District in an interview in April 2023)

It seems that under the current participation approach regeneration model, the role of government as dominant controller remains unchanged. In doing so, the political agenda is placed ahead of the interest of the people, exploiting the already marginalised group and widening the socioeconomic gaps between the lower and upper classes. Nevertheless, in China, cities like Guangzhou have managed to create more space for citizens to be better represented in urban redevelopment projects (Zhang et al., 2019). This may suggest that there is still room to be optimistic regarding Beijing’s potential to adopt a real participatory approach in the future.

References

Atkinson, D. (2008) “The Heritage of Mundane Places.” In: Graham, B. and Howard, P. (ed.) The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Hampshire: Ashgate, pp. 381-396.

Innes, J.E. and Booher, D.E. (2004) Reframing public participation: strategies for the 21st century. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(4), pp. 419-436.

Lefebvre, H. (1996) Writing on Cities. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Madgin, R., Webb, D., Ruiz, P. and Snelson, T. (2018) Resisting relocation and reconceptualism authenticity: the experiential and emotional values of the Southbank undercroft, London, UK. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24(6), pp. 585-589.

Nitzky, W. (2013) “Community Empowerment at the Periphery Participatory Approaches to Heritage Protection in Guizhou.” In: Blumenfield, T. and Silverman, H. (eds.) Cultural Heritage Politics in China. New York: Springer, pp. 205-232.

Shin, H.B. (2014) Elite vision before people: State entrepreneurialism and the limits of participation. In: Altrock, U. and Schoon, S. (Eds.) Maturing Megacities: The Pearl River Delta in Progressive Transition. Springer, pp. 267-285

Wu, F. (2016) State dominance in urban redevelopment: beyond gentrification in urban China. Urban Affairs Review, 52(5), pp. 631-658.

Zhao, P., Li, S. and Liu, D. (2020) Unequal spatial accessibility to hospitals in developing megacities: new evidence from Beijing. Health Place, 65.

Zhang, L., Lin, Y., Hooimeijer, P. and Geertman, S. (2019) Heterogeneity of public participation in urban redevelopment in Chinese cities: Beijing versus Guangzhou. Urban Studies, 57(9), pp. 1903-1919.

About the author

Ziyu Qiao is an Economic Policy Consultant at UN-ESCAP. She recently completed her MSc in Development Studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Ziyu’s broader interest lie at the nexus of inclusive urban development, rural-urban inequality, cross-border digital trade, and e-commerce.