Imagine moving to a city where the skyscrapers never end, and opportunities seem boundless, but you find yourself an outsider working hard but receiving unequal treatment simply because you are a rural migrant or one of their children. This is the stark reality for many rural families in Shanghai, a major migrant destination in China. They arrive fueled by dreams of a better future, particularly in securing a superior education for the next generation. However, the reality quickly reveals Shanghai’s educational excellence as a tale of two cities: one where urban residents have access to some of the world’s top schools and another where rural migrants confront a series of social, economic, and bureaucratic barriers that keep the city’s educational treasures frustratingly out of reach.

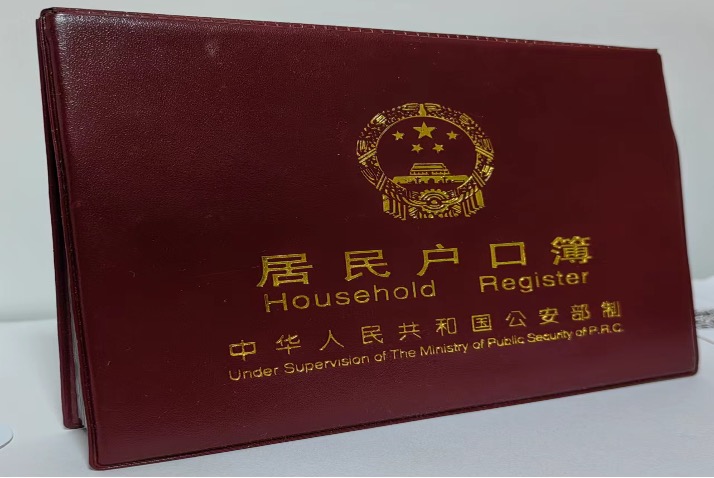

The educational plight of migrant children in China is mainly attributable to the barriers imposed by the hukou system, a household registration framework established in the 1950s (Chan and Zhang, 1999). This system classifies each individual as either a rural or urban hukou holder based on the area of their mother’s permanent address at the time of their birth (Goodburn, 2009). As of 2021, nearly 42% of Shanghai’s residents did not have a local hukou (Shanghai Statistical Yearbook, 2022). Among these residents, it is estimated that over 500,000 are children between the ages of 5 and 14, which are often considered as the golden years of educational development. Migrant workers often bring their children to Shanghai or have children born in Shanghai, motivated by the belief that the city’s better educational resources will offer their children better opportunities to ascend the social ladder and surpass the achievements of their parents, ignoring the challenges of not having a local hukou.

In China, people’s hukou is critical in determining their eligibility for the nine years of compulsory public education, which includes elementary and middle school (Schuler, 2011). Before the early 2000s, migrant children struggled to get compulsory education from public schools in Shanghai. Only migrant parents with higher socioeconomic status who could afford high extra fees or those with connections to teachers or school administrators were able to enrol their children in these schools (Goodburn, 2009). Most migrant children, however, ended up in unlicensed private schools run by other migrants that were often driven by profit. These schools typically offered substandard educational facilities; some lacked basic amenities like a blackboard, not to mention a library, computer labs, or qualified teachers. The education quality at these schools was comparable to rural schools back in their hometowns, and the only advantage was keeping children close to their parents. Despite the poor quality, the demand for schooling was so high that new migrant schools continued to pop up.

Since 2007, the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission has taken steps to improve the health and safety conditions in migrant schools. Part of their approach included shutting down many of these schools and relocating the students to institutions that met certain quality standards. In fact, each school has limited capacity, leading to instability for many migrant children, who find themselves uprooted once again. However, at this time, the good news is that the situation for migrant children began to improve due to policy changes that eased both documentary and financial requirements for enrolling in public schools (Qian and Walker, 2015; Xiong, 2015). This allows them to attend local public schools rather than having to return to their hometowns for education. Standing in the ruins of poor-quality migrant schools, rural children then choose their own ways on the challenging journey of pursuing education and dreams. By 2012, in Shanghai, 75% of migrant children engaged in compulsory education were attending public schools, while 25% were in government-authorised migrant schools (Qian and Walker, 2015).

The educational challenges for migrant children in Shanghai extend beyond compulsory schooling. Until today, despite their years of residence and education in the city, these children are not granted the right to attend local high schools, which precludes them from taking the national college entrance exam as registered students in their current city (Ling, 2015). A survey highlighted that 75% of migrant parents wish their children to continue their education at high schools in Shanghai (Yang, 2009). However, the harsh reality is that these children often have to return to their hometowns to pursue further education. Given the curriculum differences between regions, this transition can be highly disruptive, making it difficult for them to adapt and achieve better educational outcomes (Qian and Walker, 2015).

Moreover, Shanghai has substantial local opposition to expanding post-compulsory education opportunities for migrant children. Many local parents resist these changes, fearing increased competition might diminish their children’s prospects of securing university placements. This resistance complicates the government’s efforts to implement further educational reforms.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, educational disparities negatively affected migrant children’s well-being. With the shift to online education in Shanghai, more classes for migrant children were merged with those of local students, making the inequities more apparent to the migrant students (Ding et al., 2024). Teachers often perceived their responsibilities toward migrant children as lesser, especially since these students would not participate in the local high school entrance examinations. Consequently, educators tended to focus more on local students during online sessions. Policymakers also overlooked this discriminatory treatment and showed little initiative to address these issues for the same reason. As a result, migrant children, becoming increasingly aware of these biases, grew more frustrated and anxious about their futures, severely impacting their well-being (Ding et al., 2024). This is particularly detrimental for ninth-grade migrant students who are preparing to return to their hometowns to sit for high school entrance exams; their morale is affected, potentially jeopardizing their exam performance and prospects.

The education trajectory for migrant children is riddled with not only societal and institutional issues but also with heightened pressure from their own families. According to Li et al. (2024), migrant parents are seen as having higher aspirations than native residents in Shanghai for their children’s education. This is often attributed to their children’s educational achievements being crucial for securing full citizenship rights in Shanghai, including the possibility of obtaining a local hukou. However, transferring the hukou is challenging, especially for megacities like Shanghai. Under the weight of their parents’ high expectations, migrant children are prone to assume heavier responsibilities at younger ages and study harder than their local peers, sometimes in a bid to cope with the uneven educational landscape they find themselves in.

Under these circumstances, the Shanghai Education Commission has taken proactive steps over the past two decades. Notable initiatives include the 2004 policy, “Suggestions on Enrolment of Primary and Junior Secondary Schools,” which regulated public schools to increase their capacity to admit more school-age migrant children in the neighbourhoods. In 2010, Shanghai allocated $500 million to expand migrant children’s access to public schools, making it the first city to offer free compulsory education to non-locals (Yiu, 2020). Furthermore, a 2012 policy aimed to provide post-compulsory education opportunities to students whose parents held a steady residence permit, although the reach of this policy was limited (Qian and Walker, 2015). However, the gaps still exist in the equality of opportunities, quality, and outcomes of education for migrant children compared to their local peers.

Meanwhile, the present and future increases in migration to Shanghai necessitate immediate action from the government to address the frustrations and inequalities in education that fuel migrant discontent. In 2021, Shanghai’s migration growth rate jumped to 16%, more than double the rate of the previous year (Shanghai Statistical Yearbook, 2022), potentially driven by the needs of an ageing population in Shanghai and socioeconomic shifts following the initial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These high migration inflows persisted into 2022, with no detailed updates available for 2023 and 2024. But looking ahead, as Shanghai remains a magnet for migrants, the city faces ongoing challenges in addressing the educational disparities that will affect an increasing number of migrant families.

This blog highlights the longstanding issue of educational inequality faced by migrant children in Shanghai, characterised by the poor quality of compulsory education in migrant schools, lack of rights to attend local high schools, unequal treatment in schools, and immense pressure from their parents. To conclude, the future of Shanghai and its standing as a global megacity depends on empowering every child within its boundaries. If policymakers, educators, and both migrant and local parents in Shanghai can truly empathise with these children’s struggles rather than overlooking or exacerbating them, it could significantly alter the trajectories of numerous young lives currently chasing their dreams of studying. Then, rural dreams in urban Shanghai could also shine brightly, illuminating the city’s future.

References

Chan, K.W. and Zhang, L. (1999) The hukou system and rural-urban migration in China: Processes and changes. The China Quarterly, 160, pp.818-855.

Ding, Q., Wu, Q. and Zhou, Q. (2024) Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: the wellbeing of Chinese migrant children—a case study in Shanghai. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, p.1332800.

Goodburn, C. (2009) Learning from migrant education: A case study of the schooling of rural migrant children in Beijing. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(5), pp.495-504.

Li, Z., Zhu, Y. and Wu, Y. (2024) Migrant Optimism in Educational Aspirations for Children in Big Cities in China: A Case Study of Native, Permanent Migrant and Temporary Migrant Parents in Shanghai. Population Research and Policy Review, 43(1), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09845-4

Ling, M. (2015) “Bad students go to vocational schools!”: Education, social reproduction and migrant youth in urban China. The China Journal, 73, pp.108-131.

Qian, H. and Walker, A. (2015) The education of migrant children in Shanghai: The battle for equity. International Journal of Educational Development, 44, pp.74-81.

Schuler, Y. (2011) Education as a means of integration into the city: Migrant children in the government-sponsored Honghua school in Chengdu, China. PhD thesis, School of Intercultural Studies, Biola University.

Shanghai Statistical Yearbook (2022) Migration of registered population in main years. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook. Available at: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/nj22.htm?d1=2022tjnjen/E0204.htm (Accessed: 11 May 2024).

Shanghai Statistical Yearbook (2022) Permanent residents by register and age from the seventh population census. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook. Available at: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/nj22.htm?d1=2022tjnjen/E0211.htm (Accessed: 11 May 2024).

Xiong, Y. (2015) The broken ladder: Why education provides no upward mobility for migrant children in China. The China Quarterly, 221, pp.161-184.

Yang, X. (2009) Zhongshi nongmingong dierdai “yiwuhou jiaoyu” wenti. (The issue of “post-compulsory” education of the second generation of migrant workers). Shanghai Jiaoyu 05B, 6.

Yiu, L. (2020) Access and equity for rural migrants in Shanghai. In: Kong, P.A, Hannah, E. and Postiglione, G.A. (eds.) Rural Education in China’s Social Transition (pp. 175-197). Routledge.

About the author

Zhiyi Meng was a student enrolled in the MSc programme in Local Economic Development in the Department of Geography and Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in the 2023/24 academic year.